A Post Christmas Refresher of All Things Piano: Kickstart Your Learning Back into 2025

- Jack Mitchell Smith

- Jan 6

- 17 min read

A few weeks ago, I rather dangerously posted that it would be fiiiine to make piano playing more fun and inkeeping if you found that you weren’t in the headspace in the buildup to Christmas.

The problem?

The buildup to Christmas starts at the very beginning of December for many people!

Therefore, I’m going to work on the pessimistic assumption that - although you have probably found much joy in playing the piano (which is fabulous) - you might not have put as much time into practising.

So consider this blog a refresher.

Needless to say, every single one of my following points has a much more exhaustive blog post on it from the past, to which I have linked. So if you feel you need a deeper refresh on anything, make sure you click the link so that you can fully get back into piano following the Christmas break!

Fingers and Thumbs

No longer do we refer to our fingers by their actual names (thumb, index, middle, ring and pinkie - and yes, the thumb is a finger in the context of piano!).

We now dehumanise them completely and assign them a number!

Basically, thumbs are 1, and then we move up to the pinkies to reach number 5:

Thumb - 1

Index - 2

Middle - 3

Ring - 4

Pinkie - 5

It is very important to have a good instinct as to which finger is which numerically - as well as to know your left from your right - so that when your teacher asks you to play a certain note with a certain hand and finger, you can do. Not to mention that when you come to start reading music, your fingers are often notated above or below the note so you know which finger to play them with!

Learning Keyboard Geography at the Piano

C is the note that we often start out by finding because when we first learn to sit at the piano, we get used to sitting in front of Middle C.

This is the C nearest to the middle of the keyboard, naturally. But C itself is the white note that lies immediately left of the two black ones!

From here - up or down - we use the letters of the alphabet A - G in the correct order, repeating.

For example, working up from C on white notes we come to D, E, F, G and then the next note goes back to A.

Similarly, working down from C on the white notes we have B, A and then the next note loops back round to G.

Semitones, Tones, Sharps and Flats

Regardless of whether the note is black or white, two neighbouring notes is the distance of a semitone.

To stick to the white keys, E up to F is a semitone and vice verse, as well as B up to C.

Two semitones make a tone!

Therefore, any neighbouring white keys that are separated by a black one (C - D / F - G / G - A / A - B) are a tone apart.

To sharpen a note, move it up by a semitone.

To flatten a note, move it up by a semitone.

For example, the black note immediately above the white key F is an F sharp*.

The black note immediately below B is a B flat*.

*It is much more advanced - though still correct - territory to observe that there are some doublings up. For example, the white note F can - and sometimes does - get referred to as E sharp, or E as F flat - because of the above rules regarding semitones. However, at a beginner and low intermediate level you will be safe in knowing that most - if not all - of what you need to know of sharp and flat notes will be attributed to the black keys. Try not to cram more information than you need in and focus on what’s relevant!

Can you name the following notes on the keyboard? Note that there are two answers for each - a sharp and a flat! Answers at the end!

Scales and Key Signatures

Starting with the note C, moving up to the next by using white notes: C - D - E - F - G - A - B - C creates a scale.

To play these with the proper fingers, play the following fingering for the right hand:

C - 1

D - 2

E - 3

F - 1

G - 2

A - 3

B - 4

C - 5

…and for the left hand:

C - 5

D - 4

E - 3

F - 2

G - 1

A - 3

B - 2

C - 1

When you reach the top, come back down and just read the above fingerings backwards!

The Octave

Try to learn to play the scale with both hands. Start the right hand on Middle C, and start the left hand on the C immediately below. This C is 8 notes below middle C (inclusive), and a distance of 8 notes is an interval called an octave.

When we refer to an octave, we can refer to the distance between any note and the next note of the same name immediately above or below. For example, I could give the same instruction as above by saying to play the C scale hands together with your right hand starting on middle C and your left hand starting one octave lower.

In similar vain, the scale you have just played is an octave scale, because this is the total distance that it spans. So, if you are asked to play a C scale for one octave, you have just done this!

Tonality

The scale you have played above is a C scale, but the tonality defines whether or not it is major or minor.

This is a C major scale. The major key is happier and brighter.

Using the exact same fingers, try and play a scale using entirely white notes but starting on the note A.

This is an A (natural) minor scale. The minor key is sadder and more melancholy.

One of the reasons this sounds drastically different is because of its structure:

All typical scales are made up of tones and semitones.

Major scales - such as C major - start with our root note (the note after which the scale is named - also called the tonic) and move up in the following pattern:

Tone - Tone - Semitone - Tone - Tone - Tone - Semitone

Whereas the type of minor scale you have just played (a natural minor scale) starts on the root note and moves up thus;

Tone - Semitone - Tone - Tone - Semitone - Tone - Tone

Using this structure and your understanding of keyboard geography, you could apply this to any note on the keyboard and find the notes of any scale (the same fingers can be applied to quite a lot of them, but be careful! There are a fair few exceptions too…).

Relative Minor

The reason that two scales that both use entirely white keys can sound so drastically different is just because they are closely related. In fact, they are what’s called relative major / relative minor to one another.

i.e. The relative minor of C is A minor and the relative major of A minor is C.

All scales have a relative major or minor in opposition to their current tonality. To find it, you can do one of two things:

For a major scale’s relative minor, count up six or down three (inclusive of the root note):

C - D - E - F - G - A / C - B - A

For a minor scale’s relative major, count up three or down six (inclusive of the root note):

A - B - C / A - G - F - E - D - C

Key Signature

All a key signature tells us is the scale to which a piece of music is most closely related.

You will note that the scales of C major / A minor are white note based, thus are all natural notes. This means that they are not sharp or flat.

Thus, if you play a piece of music that is entirely based around white notes then it is in in either the key of C major or A minor: the answer being whether the music sounds happier (major) or sadder (minor).

Printed Music

Clefs and Notes

There are two clefs we need to worry about when we learn piano: treble clef and bass clef.

Treble clef is associated with the right hand.

Bass clef is associated with the left hand.

The reason that we associate them with a different hand for much of our playing is because of the location of Middle C.

Middle C falls in the same place above the stave (pronounced staff - the group of five lines) on the bass clef as it does below the stave on the treble clef, effectively creating a mirror image!

Therefore, all notes logically follow in each gap and space depending on whether you are going up and down:

If you wish to learn the acronyms, you can! They certainly help to pinpoint notes:

For treble clef, the lines from the bottom up are E - G - B - D - F:

Every Good Boy Deserves Favour

Whereas the spaces reading up from the bottom spell out:

F A C E

In the bass clef, the lines from the bottom up are G - B - D - F - A*:

Good Boys Do Fine Always

And the spaces reading up are A - C - E - G*:

All Cows Eat Grass

These are useful acronyms for finding notes that you’re less familiar with, but try and focus on recognising notes with familiarity. It’s likely you can identify a Middle C without much trouble, and that’s what we want for them all!

*Don’t forget that we’re in the bass clef here, so Middle C is above the stave. Therefore, the C for ‘Cows’ is one octave lower than Middle C!

The following test spells out some words! Can you spell them all?

Note Value and Rhythm

To simplify this, we’ll start with crotchets:

A crotchet / quarter note is worth one beat. A crotchet looks like the notes above: a black head (the circle) and a vertical stem (the line)

If we don’t shade the head in, we get a minim / half note. This is worth two beats i.e. two crotchets.

And now if we remove the tail, we get a semibreve / whole note. This is worth four beats i.e. two minims / four crotchets!

Now let’s go back to our crotchets:

If we add a tail (a nice little curved line coming down from the top / up from the bottom of the stem), we get a quaver / eighth note. This is worth half a beat, or half a crotchet.

If we add two tails, the quavers become semiquavers / sixteenth notes.

Quavers and semiquavers are usually grouped together in groups of four*. This is done by joining their tails together in a straight line - a beam - across the top. This is, quite simply, called beaming!

*Feel free to read this blog here to find out more as to when we do and don’t beam. It’s not something you need to know for beginner / intermediate level, but you will need to recognise them joined together. But if you crave more knowledge, read on!

Most any rhythm we would want to notate can be done so by mixing and matching various note lengths.

To get used to picking out rhythms, find the smallest note in your passage of music and try to count the whole passage using this. For example, if you count your crotchets as “1 - 2 - 3 - 4” and your smallest notes are quavers, count ‘and’ between the numbers so you can accurately pinpoint them: “1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and”.

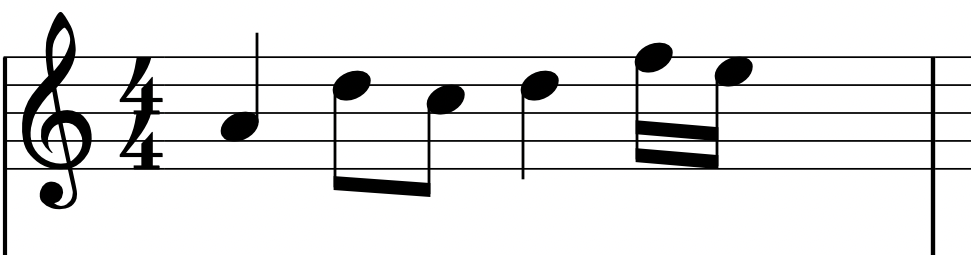

Can you identify the following rhythm?:

Note the squiggle in the second bar is a quaver rest, so it lasts as long as the quaver notes but is silence. So....make sure you count it!

Time Signature

Time Signature is displayed after the clef on a piece of notated music, and it just refers to how we count a piece of music. Do we count ‘1 - 2 - 3 - 4’ or ‘1 - 2 - 3’, for example.

The time signature is two numbers stacked above each other, the most common being 4 / 4 (sometimes this is shown as a C instead of 4 / 4!):

The top number refers to how many numbers you count in a bar. So the top number of 4 / 4 is 4! So you count 1 - 2 - 3 - 4.

The bottom number is where we have to be a tad more astute, musically, as this refers to the note value of which your counts are!

If you learn the terms quarter note, half note etc. alongside crotchets and minims etc., this should be as simple as working out a fraction. 4 / 4 = four quarters, four quarter notes = a crotchet! Which is exactly why I teach both terms!

So, if you are counting ‘1 - 2 - 3 - 4’ in 4 / 4, each one of those numbers is a crotchet. This means that each one of those numbers can house one crotchet, two quavers, four semiquavers…you get the idea!

So it’s important to get your head around these!

It’s only in more advanced music that you will get more demanding numbers at the bottom of your time signature, but 4 / 4 is extremely common, 2 / 4 and 3 / 4 are frequently used and when it is time you might introduce 8 to the bottom: 6 / 8 and 12 / 8 are especially common.

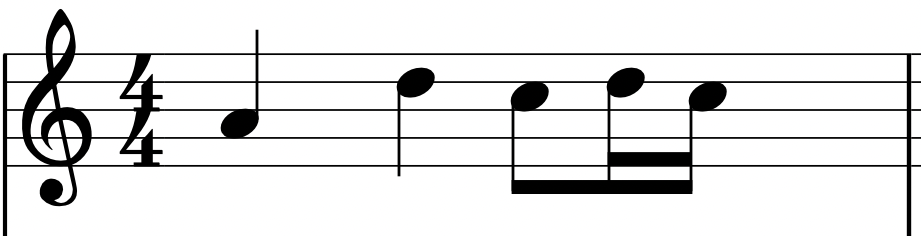

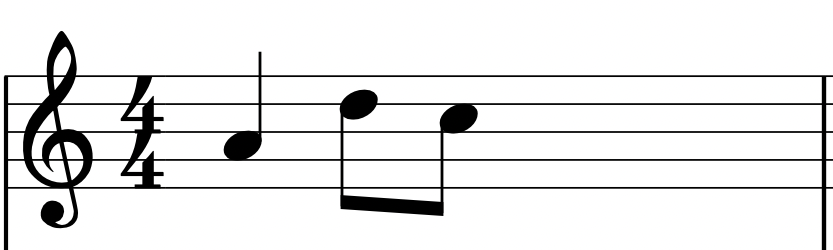

What type of notes do you need to complete the bars?:

NB I won’t be covering dotted notes on this blog, but I may write a follow up as this is all refresher!

Sharps and Flats on Notated Music

To mark a sharp on a piece of music, we use a hashtag symbol! - ♯ . This moves the notated pitch up by one semitone.

To mark a flat on a piece of music, we use a pointy, lowercase B symbol - ♭ . This moves the notated pitch down by one semitone.

When you mark the odd sharp and flat, it is called an accidental because it deviates away from the rules of the key signature. An accidental is carried on that note* for the rest of the bar unless marked with a natural sign: ♮ . This reverts the accidental back to its place in the key signature.

If no natural sign is used, the accidental only lasts for the duration of the one bar. It reverts back to its rightful place in the new bar unless or until a new accidental takes its place, and the cycle continues!

Sharps, flats and naturals are printed before the note - never after!

*There is an ongoing debate as to whether or not accidentals affect just the note of that pitch - for example, if Middle C is notated with a ♯ sign and then an unmarked C two octaves higher appears in the same bar, is that a C ♯ too or is it only Middle C that is? The general consensus - which I agree with and have seen way more evidence on scores to back up - is that only that one pitch is made an accidental, so only Middle C would be affected in the above example.

Key Signatures

Key signatures are marked between the clef and the time signature on a piece of music. They are done so by marking on the sharps or flats of the key signature.

Therefore, a piece in C major or A minor would not appear to have a key signature notated…because they are all natural notes! So establish the tonality and then you can have a better idea of which of the two your piece is notated in.

You will only ever have sharps or flats in your key signature, and they follow a very specific order!

The Circle of Fifths is a much more exhaustive topic, but have a read on this blog for more information as this will help you to sync up which scales and key signatures have which sharps!

In a nutshell, you will always add one new sharp or flat at a time in the following order:

Sharps: F - C - G - D - A - E (Fast Cars Go Driving Around Everywhere):

Flats: B - E - A - D - G - C - F (Battle Ends and Down Goes Charles Father).

For a nice, quick and easy way to find your key signature:

For sharps - find the last note notated in the key. For example, Below it is G:

One tone above G is your answer as a major key. Or, if you consider it G♯, one semitone. This makes the answer A major. Now consider that it might also be the minor key and use the A major scale to find your relative minor (see above). Remember that three notes: F - C and G - have all been sharpened.

Working up six inclusive, A - B - C♯ - D - E - F♯. So it could be F♯ minor.

For flats - strike off the last note.

For example, the last note below is D:

The new last note / the former penultimate note is your answer.

This is A♭ major. Again, it could also be its relative minor. This time, let’s work down three inclusive to find it. Remember that four notes - B - E - A and D - have all been flattened.

A♭ - G - F. So this could also be representative of F minor.

Can you identify the two possible keys for each the below examples?

Intervals, Chords and Inversions

Intervals

The distance between any two notes is called an interval.

Previously in this blog, we have already looked at one: the octave (a distance of eight notes).

We can work out simple octaves according to two notes positions in the scale.

Using the C major scale as an example, we can identify several major intervals.

C - D: major second

C - E: major third

C - A: major sixth

C - B: major seventh

Note that in each example, we count C (the root note) as 1 and count up from there to discover our intervals.

Controversially, the minor scale - such as the A natural minor we pieced together earlier - also shows us a major second as its first degree (A - B). But with this exception, it is possible to find some minor intervals:

A - C: minor third

A - F: minor sixth

A - G: minor seventh

It’s worth getting used to how these sound and also getting used to how they relate to each other in the context of a major and a minor scale, allowing you to much more quickly identify the interval as major or minor.

The fourth and fifth are neither major ‘nor minor, for these are empty intervals that don’t have a third note to define their tone. As a result, these are called perfect intervals, and are found in both major and minor scales:

C - F: perfect fourth

C - G: perfect fifth

A - D: perfect fourth

A - E: perfect fifth

Finding Chords

A simple form of a chord using three notes is known as a triad. This is a three note chord.

All major and minor triads feature the root note and perfect fifth, but in addition to this we need to add either the major or the minor third.

For example, a C major chord would be C - E - G (root, major third, perfect fifth).

An A minor chord would be A - C - E (root, minor third, perfect fifth).

The difference between a major and a minor triad chord is just one semitone, and it is the major or minor third that changes.

To change a major chord to minor, lower the major third by one semitone.

To change a minor chord to major, raise the minor third by one semitone.

Can you identify what chords the following are, including whether they are major or minor?

Chords I, IV and V

Finding the (major) triads of the first, fourth and fifth note of a major scale is a really useful tool for playing an enormous amount of music - whether than be pop, traditional, classical, rock etc. - with accompaniment.

For example, finding the first, fourth and fifth note of C major would be

C - 1

D - 2

E - 3

F - 4

G - 5

A - 6

B - 7

So; C, F and G major.

The fifth degree of a scale - in this case G - is known as the dominant, and another tool you can employ is turning it into a seventh chord. In order to do this, count seven up from this dominant note*:

G - 1

A - 2

B - 3

C - 4

D - 5

E - 6

F - 7

…in this case we have found F…

…and play it as the fourth note on top of the existing dominant (fifth) chord. So, a G major chord with an F on top: G - B - D - F, would be G7. G7 is, therefore, known as the dominant seventh of C major.

*make sure you count up seventh according to the scale you are already playing in: C major. Don’t be tempted to switch to a G major scale and count F♯ as this will lead to the wrong type of seventh chord. I may write a blog about the different types of seventh chords at a later date!

Can you identify chords I, IV and V of the following key signatures?: -

A major

D major

B major

Inversions

Inversions are really just like musical anagrams.

All of the chords you have seen so far are in what is called root position. This means that their three notes ascend in order, starting from the first note (the root).

To invert a chord such as C major: C - E - G in root position - we just need to move the bottom note to the top to play it in a slightly different order.

E - G - C. This is known as first inversion.

If we do this again with the first inversion, we get G - C - E.

This one is known as second inversion!

The reason for this is twofold:

When playing chords in the lower register of the keyboard, inversions can help give much needed breathing space as the interval between two of the notes are wider than that of root position, making the overall sound less clunky.

More importantly, it allows for us to easily change chords without having to jump our hands around into vastly different parts of the keyboard. For example, if you play a C major root position of C - E - G, you could switch to an F major second inversion instead by keeping the C and only having to move your top two fingers up to the F and A, rather than jumping up or down to a whole new position to F - A - C.

To decipher what chord something is, rearrange the notes so that you are only dealing with a standard triad i.e. note, miss one note in the scale, note, miss one note in the scale, note.

Can you identify the following chords?

In Conclusion

Whew - I think that’s it! And hopefully that’s refreshed a lot of your memory.

Before I go, however, here are some tips that you must always remember:

Keep the fingers as curved as possible whilst playing

Be delicate with the keys - don’t jab and stab at them

Always keep a good posture: sit upright with a straight back and make sure that your arms aren’t scrunched up. Sit far enough back that there is a comfortable resting of the elbows by your side whilst you play.

Learning can come in all sorts of forms: don’t rely on having to be at the piano. Practise sight reading of rhythms or pitches, draw a keyboard and try and identify the correct notes, tap out rhythms to improve musicality and much more when not around one!

Ensure you play for fun, but be disciplined enough to keep a regular practice schedule as well!

Don’t rush! Take things slowly, using a metronome if necessary. Slow practice is immensely better than rushed practice, even if it initially feels less progressive.

Enjoy welcoming the piano back into your life for 2025!

Answers

Sharp and Flat Notes:

C sharp / D flat

G sharp / A flat

F sharp / G flat

Spelled Out Words:

DABBED

CABBAGE

ACE

BEAD

Rhythm to Identify:

Football Chant - Let’s Go (Pony)

Notes to Complete the Bars:

Quaver

Crotchet

Minim

Two Key Signatures:

B flat major / G minor

E major / C sharp minor

Chords:

B major

E minor

F sharp minor

Chords I, IV and V:

A major: A, D, E

D major: D, G, A

B major: B, E, F#

Inverted Chords:

G major (1st inversion)

E flat / D sharp minor (second inversion)

D major (1st inversion)

B flat / A sharp minor (first inversion)

Jack Mitchell Smith is a piano teacher based in Macclesfield, Cheshire. Click here to find out more.

Weekly blogs are posted that may help you with your musical or piano journey. Click here to sign up to the mailing list so you never miss a post!

Comments